We need Typescript but it's not enough

Published on July 8th, 2024

🇫🇷 Article disponible en françaisTypescript is cool, but there's gaps that it cannot fix

- javascript

- typescript

- types

- type system

Few people are already convinced by Typescript. This article will not teach you new things, but I know some of y’all are looking for answers to the big question:

I’m a web developer and I just learned Javascript. Why do I need to learn Typescript? Do you hate me?

First of all, I don’t hate you. In this article, I’ll try to explain why Typescript is beneficial, based on real facts and situations. I’ll also discuss some of Typescript’s limitations. Let’s begin!

Some context

You’re a junior developer at an IT company that pays $50,000 a year in Downtown Toronto (high income earner, eh?!). You’re doing whatever you can to stay on top. You’re working on an e-commerce website. The codebase is already huge, and you’re the 59th contributor (yeah, this company’s turnover is off the charts, and managers don’t understand why).

We’re starting a new sprint (you’re in an Agile team), and you pick up a task to build a new feature to restore a user’s saved cart.

Everything is going well. At some point, you decide to code a function that returns the total discount of all items in the cart. This is how you did it:

function getDiscountFromSavedCart(cart) { const discountTotalValue = cart.cartItems.reduce((sum, cartItem) => { return sum + cartItem.pricing.discount; }, 0);

return discountTotalValue;}You’re super happy about how things are going. You were about to write some unit and integration tests, but your PM really wants this feature released TODAY. You decide to skip the tests, quickly ask for a review, and boom, your code is now in production!

Classic.

A few weeks later, your team receives a Datadog report saying that you have

15,000 alerts on your production website. The alert is about the cart discount

value being shown as NaN, which is, you know, a bit frustrating for users.

After some investigation, you realize that some catalog items have a null

value where the discount is supposed to be. So, as a 10x engineer, you push a

hotfix right away.

function getDiscountFromSavedCart(cart) { const discountTotalValue = cart.cartItems.reduce((sum, cartItem) => { if (cartItem.pricing.discount) { return sum + cartItem.pricing.discount; } else { return sum; } }, 0);

return discountTotalValue;}You run git push, the CI runs, and great work! The issue is fixed. But now,

you notice that your team is receiving a different type of error:

Uncaught TypeError: Cannot read properties of undefined (reading 'discount')For some legacy reason, some items in the catalog don’t have a pricing object

(nobody told you this, and even the client forgot about it).

You send another hotfix:

function getDiscountFromSavedCart(cart) { const discountTotalValue = cart.cartItems.reduce((sum, cartItem) => { if (cartItem.pricing?.discount) { return sum + cartItem.pricing.discount; } else if (cartItem.pricing) { return sum + cartItem.discount; } else { return sum; } }, 0);

return discountTotalValue;}But this time you’re doing things differently:

- You write unit tests to ensure your function behaves as expected for all possible values.

- You add comments to explain what

cartItemmay or may not contain.

At this point, you may have noticed that this is not a code problem but something that needs to be fixed at the organizational level. I am very aware of this, but I need a simple example to prove my point.

Typescript will help you with both points mentioned above.

Typescript does not replace unit testing, but some tests can duplicate what Typescript already validating.

How Typescript can help you?

Typescript is a language that is about 90% similar to Javascript. Some people even call Typescript a “Javascript superset.” Valid Javascript code is valid Typescript code, but Typescript code isn’t valid Javascript code. This is because Typescript allows you to add type annotations to your code.

Type annotations are pieces of information you can attach to a variable, function parameter, or function return value. They indicate the type of data (string, number, boolean, etc.) that the variable, parameter, or return value is expected to contain. You can think of it as a contract that your code must follow.

// This is valid for both Javascript and Typescriptconst user = { id: "10", name: "Christopher" };

// This is valid for Typescript onlytype User = { id: string; name: string };const user: User = { id: "10", name: "Christopher" };These annotations are used by Typescript’s compiler (an executable called tsc)

to check whether your code respects the contract you have set. If anything seems

wrong, tsc will refuse to compile your app and show you what’s wrong.

The tsc compilation output is basically your code without type annotations,

making it 100% valid Javascript.

It’s not really your code. There’s a lot of stuff added to it, depending on how you configured your project. But it is still Javascript.

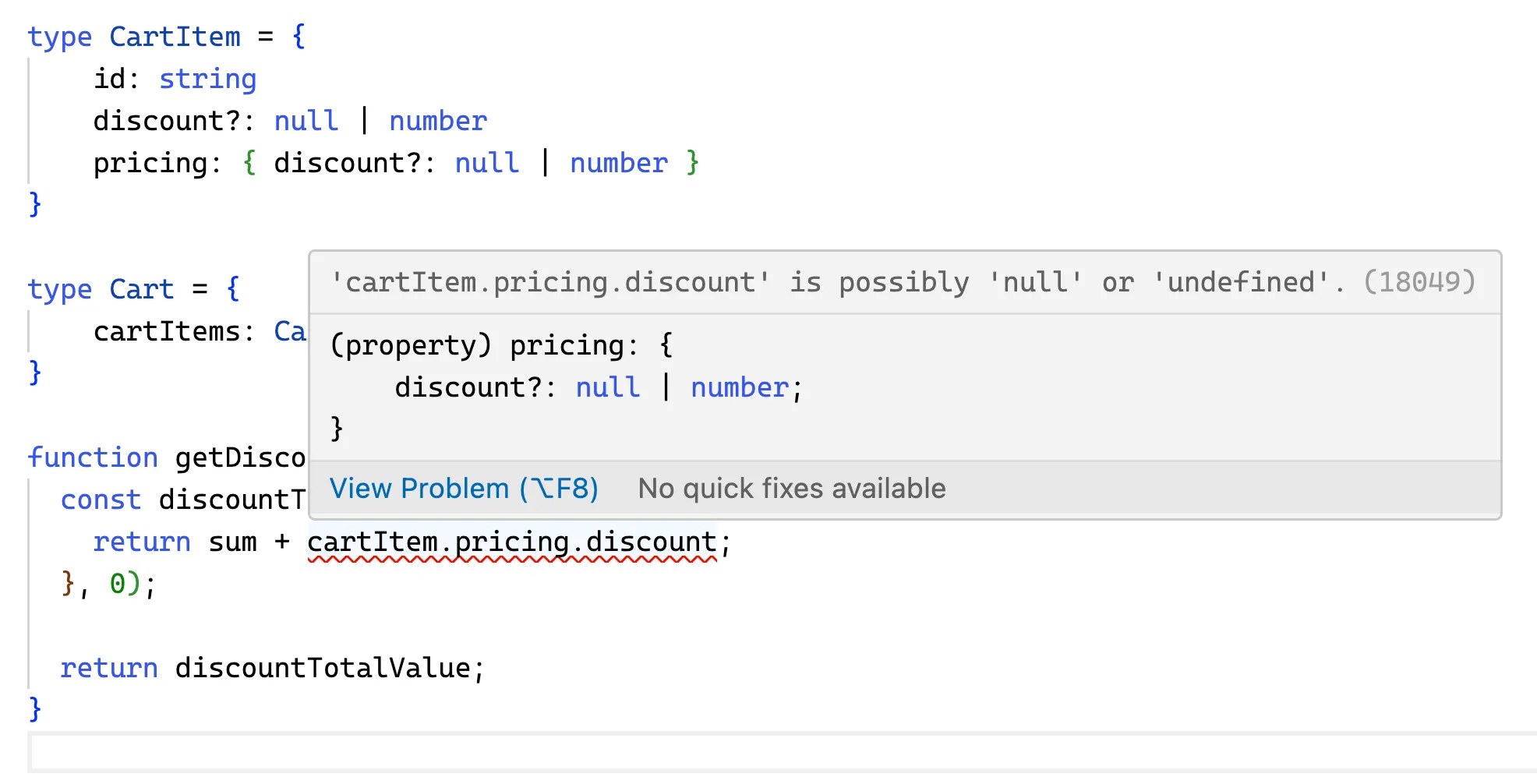

In our very first example, if the function parameter cart had a type attached

to it, we would have known that the function was not handling cases where the

data was missing, long before the code was deployed in production. The IDE would

have been able to warn us about it since Typescript works well with the

LSP Protocol.

The image above illustrates what I’ve been saying: when adding a type to the

cart variable, Typescript can let us know that our getDiscountFromSavedCart

function is error-prone.

What tsc is doing is called compile-time type checking. The compiler

checks that our code respects all type annotations BEFORE the program

reaches production. By doing so, we eliminate a whole class of bugs.

Another benefit is that the code is self-explanatory and easier to understand. Like:

type CartItem = { id: string; discount: null | number; pricing?: { discount: null | number };};

type Cart = { cartItems: CartItem[];};

function getDiscountFromSavedCart(cart: Cart) { const discountTotalValue = cart.cartItems.reduce((sum, cartItem) => { if (cartItem.pricing?.discount) { return sum + cartItem.pricing.discount; } else if (cartItem.discount) { return sum + cartItem.discount; } else { return sum; } }, 0);

return discountTotalValue;}At first glance, you can see what the variable cart is about, what it is

supposed to contain, and what the constraints are.

So, does using Typescript eliminate all bugs?

Nah.

When you’re building a real-world application, you’ll often interact with

external systems: APIs, cookies, localStorage, sessionStorage, user

inputs, etc.

In those situations, you can predict what those systems will inject into your application and then write Typescript types that match those expectations. However, we are far from compile time at this point, and Typescript cannot ensure correctness.

This is one of Typescript’s biggest limitations compared to other type systems: once your application is running and performing I/O, you’re again exposed to the kind of errors we were trying to avoid initially. What you need now is some runtime type checking.

The goal here is to create a function, a validator, that will check everything going into your application at runtime. There’s libraries you can use, like:

Some of them can generate a Typescript type directly from validator, which comes super handy.

Here’s an example:

import { z } from "zod";

const cartItemValidator = z.object({ id: z.string(), discount: z.union([z.null(), z.number()]), pricing: z .object({ discount: z.union([z.null(), z.number()]), }) .optional(),});

type CartItem = z.infer<typeof cartItemValidator>;

const result = cartItemValidator.safeParse(foreignData);if (result.success) { const cartItem = result.data; // Do something I guess?} else { // Show an error or something}As you can see, I’m using Zod here. I have a validator cartItemValidator

which sole purpose is to check if any data corresponds to the shape I expect for

a CartItem object. This check is done at runtime, when the data comes from

whataver external source, like the localStorage. Zod even gives you a way to

generate a type from a validator; best of both world.

Not everything is perfect

Now that I’ve tried to sell you on Typescript, let me give you some points on why it might be a bit of a pain point.

All or nothing

You need to go all in and make sure everything is typed. If you miss a single function or variable, you put your whole system at risk. Typescript is super permissive, so allowing gaps can be tempting sometimes.

any type

As I said, Typescript is permissive. It gives you a type any, which allows for

data of any type. It’s sometimes used as a quick escape hatch when things get

harder to type. By using it, you’re disabling type checking and opening the

door to unexpected behaviors.

Tooling

When creating a project or a new web app, your goal is to go as fast as possible. If you want to use Typescript, you’ll have to install it, configure it, and ensure it works your way. Configuration is a big pain point for many people, as it’s not only Typescript but also all the libraries you use within your project. You might find yourself at times fighting against the type system.

Verbosity

Your (unsafe) Javascript code used to be concise but now with types, it seems like a lot of noise. It’s also technically more work, more things to write. Try to see this constraint as a tradeoff you’re making for safety. And to be honest, for most of the cases, Typescripr type inference, is enough and will avoid you douing a lot of manual typing.

So, should I still go with Typescript?

Definitely!

I truly believe that the benefits outweigh the drawbacks. I’ve been using it since 2015, and it’s been one of the main drivers for my growth and career. It also opened the door for me to explore frontend solutions to unsafe Javascript, such as:

You should go, and give it a try. Here’s some resources to help you get started: